Supply chain managers have no peer in understanding the complexity of the global economic and regulatory environment. And, they are well positioned to expedite a cutting edge approach to public-private security cooperation. By Patrick Burnson December 09, 201 Supplychain247.com

According to a recent report issued by the Stimson Center in Washington, DC, new forms of global illicit trafficking threats mean that public-private security partnerships are even more important. Nate Olson, a research associate for the Managing Across Boundaries Initiative at Stimson, maintains that reliable data on global contraband flows is “notoriously evasive.”

One estimate, he says, puts the total annual trade in illicit goods, excluding money laundering, at $650 billion. Illegal narcotics, along with counterfeit pharmaceuticals and electronics, accounted for roughly half.) But in quantitative and qualitative terms, there’s little doubt that the problem is serious and growing.

Whether they deal in drugs, counterfeit products, or weapons, decentralized criminal and terrorist networks are co-opting the same physical and informational infrastructure that enables legitimate trade. “They’re moving at the speed of 21st-century commerce,” says Olson.

Related: From Mexico to the Midwest, a heroin supply chain delivers (external link)

Unintended Consequences

Stimson analysts add that this hasn’t stopped governments from trying to bring cross-border trade more within their reach through the usual countermeasures of customs enforcement, intelligence gathering, and industry mandates.

Yet even when the policy objective is laudable, using the traditional tools alone are often inadequate, and the report indicates that they can have unintended consequences. For example, new disclosure requirements related to minerals from conflict-affected areas impose what many regard as “unrealistic” diligence standards on firms far downstream in supply chains for electronics.

Rather than risk legal entanglements, Olson observes that some of those firms might choose to sever trade relationships with all suppliers in the affected regions. “The fallout hopefully would see a reduction in illicit commodity flows, but it certainly would include constraints on legitimate commerce throughout the supply chain,” he adds.

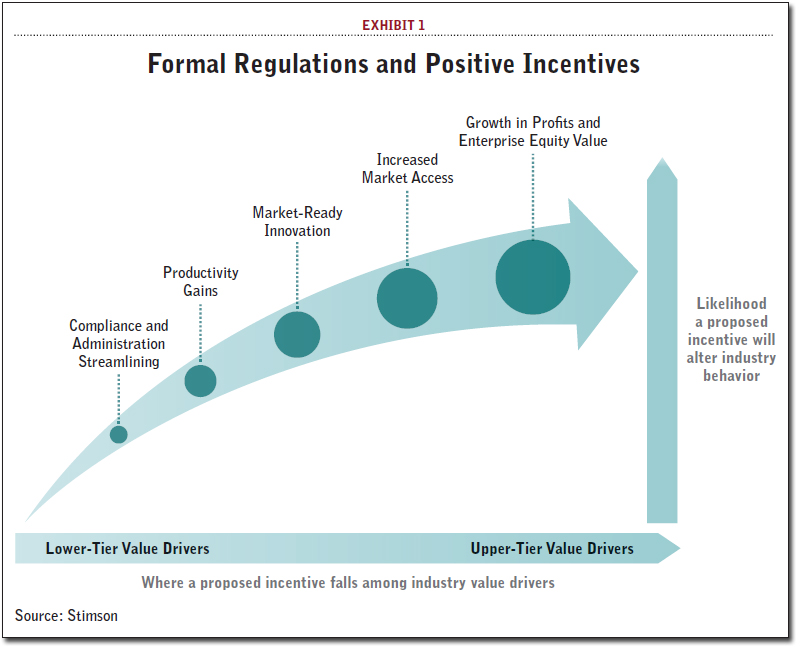

The corollary is that security today is less directly tied to being a Cold War-style superpower. It’s increasingly tied to “Market Power”—leveraging the private sector’s capabilities and expertise to serve the public interest without undermining economic competitiveness. Among other steps, that means complementing formal regulation with positive incentives for legitimate industry (Exhibit 1).

Complementing formal regulation with positive incentives for legitimate industry is a key part of modernizing public-private security operations.

As the connective tissue among disparate legal jurisdictions, business models, and geographic locales, supply chain management is vital to modernizing public-private engagements. For more than a year, firms from this sector have been part of a dialogue to shape practical implementations. Their ideas cut across three mutually reinforcing themes— three “asset classes” in a public-private portfolio that can both unlock value for industry and better support government security goals.

Create a Checklist

Stimson analysts recommend that the trio of asset classes should be measured and categorized. Here is a brief overview.

- Leveraging Value-Added Information. Stimson recognizes that supply chain managers hold a clear comparative advantage over government counterparts in collecting, disseminating, and interpreting the data at their disposal. Innovations in “track and trace” technologies, like RFID tags and next-generation GPS systems, are allowing much greater visibility into how goods and information move through the pipeline. Enhanced tools for analytics and risk management also show promise. Even when operating strictly in the open-source domain, these capabilities can make further inroads against illicit trafficking in the coming years. Furthermore, supply chain managers could see even greater returns of their own as they identify new opportunities to dovetail data with adjacent industry spaces like port and warehouse operations, analytics and ratings services, and even insurance.

- Building Cross-Functional Capacities. Data sharing is only one potential area of deeper cross-functional cooperation, both across and within companies. A recent report from an industry advisory body to the U.S. government underscored in stark terms how the private sector, despite its relative agility, suffers from coordination problems with serious consequences. “The limited horizontal integration of [the licensing, import, export, and logistics] competencies is the source of many misunderstandings,” say analysts. “These misunderstandings typically result in shipment delays, increased risk, and unnecessary exposure for a company.” There, in a nutshell, is the business case for more integrated mechanisms. The security case is equally strong. Many of the illicit trafficking challenges that will compel public-private approaches in the years ahead will require organizations of disparate specialties to pool capabilities and expertise. For supply chain managers, it might make most sense to start by focusing these efforts in intermodal environments.

- Strengthen “Trusted Trader” Networks. The third area ripe for mutual gains is a set of next-generation “trusted trader” regimes. This offers the most direct means to complement traditional government oversight and enforcement with decentralized, industry-embedded incentives for increased diligence. Government-driven efforts internationally to develop and harmonize Authorized Economic Operator (AEO) programs are important, but again insufficient. In the U.S., the continued exclusion of certain 3PLs from the Customs-Trade Partnership Against Terrorism is one example of government’s inability to align with contemporary business models. The real game-changer here would be more proactive industry participation in the design, implementation, and even administration of these networks.

Olson says that taken together, these three areas represent a compelling value proposition for supply chain managers.

“For government, they represent a natural starting point in building a broader public-private portfolio of tools for managing contemporary security challenges,” he says.

“It is vital that the industry remain engaged to ensure that the actual implementation of these more innovative governance tools remains consistent with profitability in global business operations.”