An organization rushes into an inventory reduction project; then, it quickly moves on to capacity usage improvement, followed by customer service enhancement, then to supply chain cost reduction. Eventually, the company circles back to where it started—inventory.

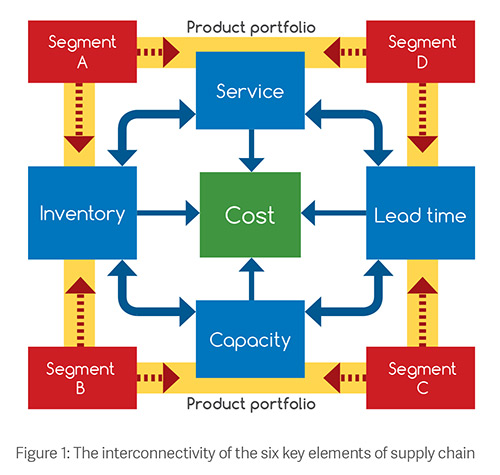

Sadly, few professionals realize that the six key supply chain elements—cost, capacity, inventory, lead time, customer service level, and product portfolio complexity—are inextricably intertwined. (See Figure 1.) As such, they should be managed as pieces of a whole. Supply chain management is a balancing act that aims to achieve the best combination of elements to support the overall business strategy and meet customer expectations. Finding a balance is key to avoiding costly vicious cycles.

Of the six supply chain elements, three are considered critical operational resources: capacity, inventory, and lead time. These elements act as buffers against demand fluctuations and protect businesses from lost sales due to out-of-stock products. Maintaining these buffers is essential to managing uncertainty. Potential areas of concern include demand, raw materials supply, factory performance variations, and quality problems. Consider the critical operational resources as a company’s first line of defense against business uncertainty.

Industries take various approaches to critical operational resources. Consumer packaged goods companies often use inventory safety stock as protection against uncertainty in demand and, often, supply. Meanwhile, telecommunications businesses and utilities typically treat the capacity buffer as finished goods—intangibles such as data packets and kilowatt hours that cannot be kept in inventory as toothpaste or automobiles can. In industries such as aircraft and military equipment manufacturing, where customers are willing to wait a long time to receive delivery, lead time often becomes a natural buffer.

Supply chain and operations management professionals must understand and be able to quantify the linkages between the lead time promised to customers, the capacity usage required to enable that lead time, and the safety stock necessary to deliver at the specified lead time and capacity. Senior management, of course, wants it all: the highest capacity usage; the lowest inventory levels; and the shortest, most reliable customer lead times—all this coupled with the highest customer service levels; the broadest product portfolio; and, most importantly, the lowest cost.

Managing the six elements of supply chain is a bit like squeezing a balloon: Apply pressure in one place, and it pops out on the other side. Finding the optimal balance can be difficult to achieve, as the elements are disconnected organizationally. In the typical environment, production oversees manufacturing capacity, sales or supply chain handles inventory and service, marketing manages the product portfolio, and so forth. This frequently leads to one or more of the following scenarios:

- Capacity usage is pushed too high, resulting in chronic stockouts.

- Depleted inventory causes order-to-delivery lead times to deteriorate, and production enters a tailspin of nonstop expediting and rescheduling.

- Lead times shorten, adversely affecting stockouts and capacity usage.

- Overexpansion of the product portfolio taxes capacity and inventory levels.

The results are obvious, but potentially devastating: dissatisfied customers, empty shelves, lost sales, and plunging profits.

Trouble at GlobeCo

Consider the case of a large, global electronic components manufacturer we’ll call GlobeCo. This company operated on a rather manufacturing-dominant philosophy, where achieving the highest

possible production capacity was viewed as a prime success factor—and was well rewarded. Inventory was set at a “good-enough” level of 24 days of sales for finished goods and 15 days of consumption for raw materials and components.

GlobeCo suffered from long and unpredictable customer lead times, with average fill rates ranging from 45 to 70 percent. Customer demand was seasonal and highly volatile, requiring either a large capacity or finished goods inventory buffer. However, manufacturing capacity was planned with no regard for seasonality and short-term variability. The planning department emphasized high production capacity usage, but examined only the annual demand data—a straight-line value that does not reflect seasonality.

Thus, manufacturing was left with no capacity buffer to accommodate seasonal demand spikes and short-term volatility. Between January and July, factories fell hopelessly behind schedule. From August to December, when demand dipped, manufacturing would begin to catch up on back orders, only to start the expediting race anew in January.

The professionals at GlobeCo soon learned the importance of evaluating a variety of potential solutions for feasibility before immediately doubling capacity or tripling inventory levels. It became clear that the decision makers would benefit from considering

adding internal or external capacity to absorb short-term demand spikes

carrying higher levels of finished goods or raw-material inventory; for example, pre-building stocks during the off season

negotiating with customers to allow for longer lead times, which can have the same effect as boosting capacity

finding a balance of the three, optimizing through differentiation based on products, customers, types of capacity, and other business aspects.

Leaders at GlobeCo examined their options and analyzed the potential results of the various approaches.

Increasing capacity only. One of GlobeCo’s functions with the worst service ratings—a stamping operation—was chosen for this proof of concept. It was determined that, with lead time set at 30 days, the stamping operation would have to add three stamping machines and one additional tool to achieve a 95 percent service level. This would increase the plant’s annual controllable costs by $320,000 in labor and depreciation.

Increasing inventory only. Analysis of the required finished-goods inventory to achieve a 95 percent fill rate would cost GlobeCo an incremental $105,000 per year in storage and carrying costs, an increase of nearly 200 percent.

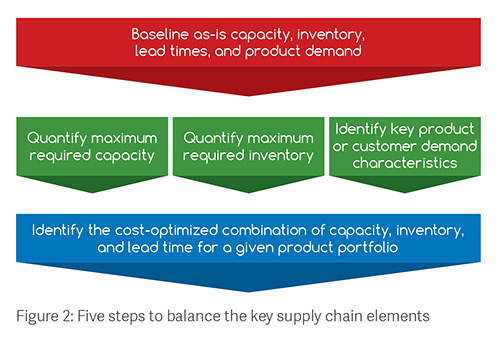

Combining the two. Based solely on the preceding analyses, it would appear to be significantly more cost effective to add

finished-goods inventory than to invest in additional stamping capacity to reach targeted lead time and service levels. However, combining the two approaches often yields better results. See Figure 2 for a five-step method of determining the optimal combination.

At GlobeCo, demand for high-volume, low-volatility electronic components could be met from finished-products inventory, ensuring sufficient buffer to achieve the desired 95 percent fill rate. Meanwhile, components characterized by low volume and high volatility could become pure make-to-order products. The plant still would need to ensure it had sufficient capacity headroom to meet the desired 30-day lead time, but it would not have to maintain finished goods inventory. Based on an optimization analysis, carrying finished-goods inventory of components with volatile and unpredictable demand would require substantial safety stock for a 95 percent service level. Considering the short life cycles of these components, as well as their hard-to-forecast demand, the result almost assuredly would be obsolescence and inventory write-offs. Thanks to the nature of low-volume parts, however, the additional capacity required for the operation to achieve a 95 percent service level is relatively small.

Looking at lead time

Lead time, as a key supply chain element that directly affects customers, often is treated as a given and seen as determined by competitive market forces. Thus, companies focus on optimizing internal elements (capacity, inventory, and costs) before attempting to modify customer-facing elements such as lead time, service level, or product portfolio. However, when changes to capacity and inventory lead to

exorbitant costs or excessive working capital, lead time becomes a potential area of consideration. Understandably, customers tend to dislike longer lead times, but sometimes they will accept the trade-off if it results in improved delivery reliability or even reduced unit price.

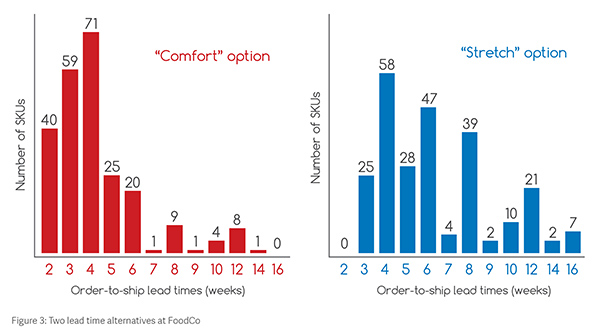

A global food manufacturer decided to go this route when it maxed out its capacity usage and could not afford additional inventory due to capital investment limitations during the economic downturn. With customer service levels in freefall, “FoodCo” had two options in front of it: Change its policy of promising customers an unrealistically short lead time or reduce its product portfolio.

FoodCo’s leaders chose a combination of the two. For each stockkeeping unit (SKU), the sales, marketing, supply chain, and manufacturing departments helped develop two alternatives for increased lead times. The first was the so-called “comfort” lead time, named this way because most stakeholders were comfortable with it and expected limited negative effects to customers. The second option stretched the limits of acceptability and was referred to as the “stretch”strategy, representing a point beyond which customers were expected to see significant material impact on their businesses. (See Figure 3.)

While reviewing its SKU lead times, FoodCo took a hard and honest look at its product portfolio and its level of true product differentiation in the market. The company pruned its portfolio substantially, which helped improve overall customer service levels for the remaining SKUs and required no additional investment in capacity and inventory.

The strategic value of the six elements

Sustainable, systemic optimization of the six elements of supply chain often requires that appropriate capabilities be built into enterprise resources planning systems. Unfortunately, these enhancements are years away at best. Therefore, ongoing optimization still is the unique privilege of only the most advanced companies.

The good news is that, as the elements are relatively stable at the majority of organizations, periodic optimization every two-to-three years is probably sufficient to ensure operations at or near the optimum balance point. A more valuable aspect of the “six elements” concept might not the optimization itself, but the cross-functional conversations it initiates. These dialogues can generate an understanding of the interconnectedness of supply chain elements throughout the organization. For example, the effectiveness of the sales and operations planning process will improve immeasurably if everyone clearly understands that no supply chain element can be changed without affecting the others. This also can boost the effectiveness of corporate improvement initiatives, as employees will stop squeezing the balloon and begin to examine all supply chain elements in tandem.

Vadim Kapustin develops global pricing strategy and improves customer insight capabilities at Walmart. He has professional experience in strategy, supply chain and operations, and entrepreneurship. Previously, Kapustin was a principal at A.T. Kearney, where he helped global Fortune 500 clients in the areas of supply chain strategy, manufacturing, warehousing and distribution, strategic sourcing, and business turnarounds. He may be contacted at vadim.kapustin@wal-mart.com.