The skills needed to do the supply chain job keep evolving. The fundamentals learned in the classroom or in early job assignments are still relevant, but they need to be revisited and reinvigorated within the context of today’s challenges. By Art van Bodegraven & Kenneth B. Ackerman May 09, 2013 supplychain247.com

We talk glibly about change in supply chain management – continuous change, managing change, coping with change, even leading change. For all too many of us, those are only words. Truth is, though, that change in our universe is real, fundamental, and visceral.

As definitions of supply chains change, always extending and expanding, far behind are the days when our world was all about quoting rates, tendering loads, and pick/pack/on-time-shipment performance.

As we have been required to get proficient in customer service, sourcing and procurement, supplier relationships, Sales & Operations Planning processes, and even occasionally integrating manufacturing to round out our planning and execution responsibilities, some of us have staggered a bit under the load.

We have bad news. Staggering under the load of these new supply chain requirements is no longer an option; we must master all of these elements as well as new ones that are certain to emerge.

Some may see these new opportunities for sleepless nights as “soft” skills – not quite as important as the “hard” quantifiable execution tasks we traditionally have focused on.

We have more news. The soft stuff is surprisingly hard to execute, and it just may be the key to consistent and sustainable performance on the hard stuff.

So, what are the most important of the new basics? We discuss a number of them in this article; but be assured that the list will continue to grow.

The scope and scale of supply chain management may not be infinite, but like galaxies in our celestial universe, they will continue to expand.

The Role of Leadership

Perhaps the one basic that is fundamental to all others is leadership – which is different from the traditional focus in supply chain on “management”.

Nothing happens without leadership, whether it is in SCM or in any other aspect of organizational life.

Leadership is the continuous process of enabling your people to achieve more of their true potential in a positive, sustainable way.

Leadership differs from management in several important respects:

- Leaders do the right thing; managers do things right.

- Leaders innovate; managers execute.

- Leaders develop; managers maintain.

- Leaders ask “why not”?; managers question “why”?

- Leaders focus on people; managers concentrate on systems and structures.

- Leaders exhibit trust; managers exercise control.

- Leaders look toward the horizon, a long-term vision; managers point to deadlines, a short-term focus.

- Leaders set objectives; managers organize the path to their accomplishment.

The reality is that both leaders and managers are necessary for business success. Having the right mix of individuals in the organization is the key. It’s important to note, too, that there is some overlap in the skills required of each group.

Both leaders and managers should be teachers; both should be clear and unambiguous communicators. Both can be genuine “people persons.” And both can be masters of conflict management.

This last point about conflict management merits further comment. Doris Kearns Goodwin’s best-selling book Team of Rivals tells how and why Abraham Lincoln recruited his political enemies to serve in his cabinet. Lincoln’s leadership genius was his ability to convert fighting into “constructive conflict”.

Debate and disagreement can be part of the leadership process, as long as the leader is able to skillfully convert conflict into compromise. Managers today should welcome constructive conflict as part of the process of finding creative solutions to complex supply chain challenges.

Finally, today’s supply chain professionals can learn from the concept of servant leadership, which was first described by R.K. Greenleaf four decades ago. One of its most famous champions was Sam Walton, founder of Walmart.

Sam drove an old pickup truck, flew his own small airplane, and inspired hundreds of workers when he asked: “Who is number one? The customer!” Both Greenleaf and Walton recognized that the best way to ensure that customers are treated well is to also treat your workers very well.

Herb Kelleher, founder of Southwest Airline, described it this way: “Management has its customers, the employees. If the employees are not satisfied, they will not deliver the required performance. If the customers are not satisfied, they will not fly again with Southwest.”

The servant leader submerges his or her ego to facilitate the success of followers.

There are differences between leading and driving. You drive a car, but there is a limit to how far you can drive people. Leaders focus on their people, and drivers focus on themselves. Drivers emphasize compliance, while leaders encourage autonomy. Drivers seek to control, while leaders encourage engagement and empowerment.

The New Diversity

Just as the nature of leadership is changing, so is the nature of the workforce to be led. Time was (and not that long ago) that diversity meant having women and people of color in roles historically reserved for Caucasian males. Today, and certainly going forward, workforce diversity has become much more expansive.

In addition to the traditional male-female breakdown, gay, lesbian, and transgender persons are now part of the diversity mix. Racial diversity has expanded beyond a single ethnic group or groups to include a rich tapestry of ethnicity, national origin, and religious practice and preference.

We now have in our cities and even smaller towns, significant populations of Latinos, Central/Eastern Europeans, Somalis, Vietnamese, Haitians, Indians and Pakistanis, and many more—a significant number of whom are working in supply chain-related jobs.

Today’s diverse workforce presents special challenges in management, communications, assimilation and accommodation of cultural and religious practices. Managers need to step up to this challenge because these individuals bring much-needed labor and brain power to our workplaces.

We can no longer hang out a 21st-century equivalent of “Irish Need Not Apply” signs to discourage or exclude recent immigrants.

One of our greatest diversity management challenges, though, may lie in the several generations that are present in the modern workplace. The media talks as if the Baby Boomers are all retiring at once; yet the realty is that many will stay in the workforce for a number of years. (Some of their predecessors, your co-authors included among, will still be working, too.)

The Gen Xrs are not that new any longer; in fact, some of them are contemplating retirement. And the Gen Y Millennials have been coming into the workforce for a few years. The message: We as supply chain managers must find ways to get these disparate groups to work and play well together.

There is another component to the multi-generational, multi-ethnic supply chain workforce that is likely to grow – and appropriately so. Walgreens, beginning with their Anderson, S.C. distribution center, has provided us with the template for building a unified workforce that includes people with handicaps – physical, mental, emotional, or some combination.

The company has made an enormous effort to design their facilities and processes so that these individuals can work effectively with no compromise in business performance.

Bottom line: managing, leveraging, and integrating these disparate workforce components is vital to our future success in getting enough resources to get the job done, and using those resources with optimal effectiveness.

Green as a Way of Life

Going forward, people in our profession will have to think of themselves as sustainability managers as much as they are supply chain managers. It’s inevitable, and sooner than we may think, that green principles will be embedded in supply chain education and in day-to-day practice.

A few short decades ago, green was perceived to be the province of tree-hugging idealists – not practical, not economic, not feasible. Today, it is mainstream, and has become a critical focal point in the boardroom.

Some green initiatives like recycling and have been pursued for decades. Other no-brainers such as motion-activated lighting systems took a little longer to catch on. In the past few years, though, the momentum toward greener, more sustainable supply chains has accelerated.

Happily, there are scores, maybe hundreds, of companies experimenting with all kinds of technologies and practices to reduce emissions, shrink the carbon footprint, and manage consumption in a more sustainable manner. The high-profile initiatives may or may not be right for a specific company, or a specific geography, but they do capture public and political attention.

Prime examples are the alternative and/or auxiliary power sources of wind and solar. The solar option can range from small arrays on the roof of a distribution center to vast farms of panels. Wind can vary from a simple roof-edge application, to a single standalone tower, to farms of towers.

As the research and engineering into these energy sources proceeds, you get a sense that what’s old is new again. Think about the days when every farm had a windmill!

We will all be green sooner rather than later – whether we get there on our own accord or be led kicking and screaming by Federal and state governments. From our perspective, the former path is far preferable.

It makes eminent sense to start off with the green projects that have a bottom line payback now, rather than wait for governments to dictate that we do things that may or may not pay off in a reasonable period.

We mentioned earlier that many companies are working on various sustainability initiatives. Two that have had considerable success in a supply chain context are Murphy Warehouse Co. and GENCO.

Murphy Warehouse, a Twin Cities-based multi-facility service provider, has successfully implemented many sustainability initiatives that make business sense, including:

- LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) design and conversion at their facilities, at a near-trivial increase in cost per square foot.

- Auxiliary solar power supplying 18 percent of power with a four to five year payback.

- Storm water runoff elimination, with a projected payback of eight years.

- Prairie grass landscaping, with an 85 percent cost/acre reduction and minimal investment.

- Brownfield redevelopment of an EPA Superfund site, providing habitat for eagles and native fish

- Forklift tune-ups and quick-charge batteries to reduce gas emissions and increase in-use productive time.

- Green roofs with vegetation cover; dock blankets for a 10 percent heating expense reduction.

- T-8 lamp installation, reducing energy cost by 4 percent.

GENCO, the well-known product life cycle solutions provider, has made a deep and wide green commitment throughout its operations. The range of their initiatives is expansive.

GENCO has been working hard on energy reduction, lighting control and upgrades, alternative fuels, process design/re-design, overall supply chain design, and reverse logistics applications. Sadly, not all that shimmers is green.

The term “greenwashing” was coined back in 1986 to describe deceptive practices designed to enhance the eco-friendly image of organizations and products.

The so-called seven deadly sins of this practice are:

- Hidden tradeoffs—branding something as “energy efficient” but failing to mention a hazardous content.

- Absence of proof—making a green claim either with no certification or with a certification from some bogus authority.

- Vagueness—claiming something is “100% natural” though it actually contains naturally occurring toxins.

- Irrelevance—for instance, proclaiming a product to be “CFC-free” when CFCs have been banned for decades.

- Lying—making a flat-out false claim.

- Masking a fatal flaw—touting “environmentally friendly” pesticides that actually kill birds would be an example.

- False labeling—such as subliminally suggested purity or implied endorsements. Think about a sparkling waterfall on the label of a bottle of purified municipal water.

We need to understand that cradle-to-grave—even cradle-to-to-cradle—logistics is fast becoming a way of life. Tomorrow’s winners will develop a strategic commitment to sustainability, which will require excellence in all elements of supply chain planning and execution.

We Are All Numbers People

One of our greatest shortfalls as a profession has been the failure to learn and operate within the CEO’s frame of reference. In thinking about the “new basics” of our work, we must address this gap immediately.

We like to talk about things like perfect orders, on time shipments, unit supply chain cost, inventory levels, and stock-outs. Guess what? The CEO doesn’t really care about these.

Oh, he or she might be swayed by the CFO to think about inventory is a quick source of ready cash. But top management’s real hot buttons are Return on Assets (ROA), Return on Investment (ROI), Return on Equity (ROE), Gross Margin or Earnings Before Taxes and Depreciation (EBITD). If those terms are not part of your vernacular, you need to learn them fast if you want to be taken seriously within the business.

Frankly, too many supply chain practitioners make the situation worse by undervaluing how and where we contribute to the company’s top-line financial performance.

We become over-focused on inventories – in particular, the need to cut them. We concentrate on trimming costs in small increments by demanding more out of the workforce or by squeezing suppliers.

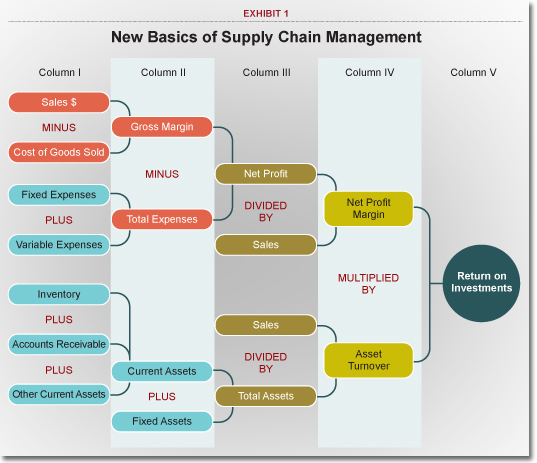

The fact is that we affect most, nearly all, of the components of enterprise performance. These are probably best illustrated in the well-known DuPont Model analysis, shown in Exhibit 1.

The model’s interactions are summarized in the exhibit. Its power lies in highlighting the many areas in which supply chain management materially contributes to an enterprise’s financial performance.

As the model shows, supply chain planning and execution – and decisions – have profound effects on sales, cost of goods sold (COGS), fixed expenses, variable expenses, accounts receivable, and, hugely, fixed assets.

And, yes on inventory…but not necessarily to cut, but to make sure that inventory is at the right level for a balance of investment and service. All of these pieces together are used to calculate gross margin, total assets, net profit, asset turnover, and return on assets (and return on equity), and so forth – in other words, the things that keep the CEO up at night.

When we run supply chains in the context of the enterprise’s performance, we are invited to a seat at the grown-up’s table. This represents the coming of age in the corporate structure.

Mastering Relationships

Supply chain professionals must become masters of something they probably never studied in school: relationship management. We have so many interactions to manage today…suppliers, customers, service providers, consultants.

And those are just those on the outside. We also have deep and wide relationships within our organizations – internal customers, sales and marketing, legal, real estate, IT, finance and accounting, C-Level officers, and sometimes even board members. And, let’s not forget governmental relationships at Federal, state, and local levels.

Are business relationships in general and supply chain relationships in particular, different from just plain “relationships”? How do we initiate them? What keeps them going after the first blush of infatuation? Are they all that important?

In the last century, one could have made the argument that relationships didn’t matter all that much. We operated in siloes within the organization. Outside, we had transactional, often adversarial, dealings.

But today, we have entered the Era of Collaboration in supply chain management, or at least that’s what the experts tell us. But we submit that collaboration without the foundation of a sound business relationship is extremely difficult.

Sustainable collaboration is not simply about “making nice” with customers and suppliers. Rather, it’s built on a foundation of disciplined and rigorous practices and processes designed to foster win-win behavior over long periods of time.

The mantra that supply chains compete against other supply chains can be turned from slogan to reality through thoughtful relationship management. However, this is not about traditional sales/purchasing feel-good adventures with golf and drinks, dinner and drinks, or drinks and drinks. Such “relationships” are superficial, transient, and fragile.

Neither is it necessarily about “partnerships”. A true partnership has attributes of high trust, close communications, shared values, open books, common objectives, and mutual benefit. So while honesty, courtesy, and clear communications should be part of any business relationship, these qualities do not necessarily add up to a partnership.

This holds true for both suppliers and customers. The secret to figuring out where to invest in deeper relationships lies in hard work, constant maintenance, and frequent re-evaluation.

Both customers (key accounts) and suppliers (partners) must be selected on the basis of a structured analysis of mission-criticality, future prospects, alternative suppliers or customers, and overall business value. This entire process of relationship building is arduous, but vital.

We’ve observed seven building blocks that lead to a successful outcome:

- A chemistry of shared values and compatibility.

- Close attention and frequent feedback.

- Belief in and commitment to the process and concept of the relationship.

- Continuous improvement—Kaizen—in all aspects.

- No assumptions; nothing taken for granted.

- Recognition of the other party’s vulnerabilities.

- An investment perspective vs. a cost mentality

Strategy and Planning

The last two “new” fundamentals are the closely related activities of strategy and planning. Supply chain professionals today need to be proficient in both.

Strategy provides the “why” behind the “what” of supply chain operations. Many managers fall into the activity trap. They get so involved in doing that they overlook the strategic issues that should be the drivers of their actions.

Supply chain professionals need to understand that difference between tactics and strategy. Tactical decisions are the process of doing things right; strategic decisions are doing the right things.

In football, blocking and tackling are the tactics, and the game plan is the strategy. In military life, the battle plan determines the tactics while the war plan lays out the overarching strategy.

As C.L. Dodgson (aka Lewis Carroll) observed in Alice in Wonderland: “If you don’t know where you’re going, then any road will take you there.”

There are six questions that should be asked in defining your organization’s strategy:

- What business are we really in?

- Who are our preferred customers?

- What is our “special magic”?

- What do our customers think of us?

- How will we survive?

- What is our culture?

In addressing the first question, consider that the answer may not be as obvious as it may seem. Southwest Airlines, for example, believes that its real business is not air travel but rather customer service.

So if our real business is customer service, we must have exceptional customer-centric processes that distinguish among customer classes and types and reflect an investment (long term) perspective rather than a transient cost viewpoint.

For supply chain executives, the main point is to support the business objective – whatever it is – in all activities and programs.

Preferred customers are those that offer the best business relationship over the long term. For these customers, we must have tailored products, service levels, and processes that encourage them to do business with us. (For the less-desirable customers on the other hand, we should not offer anywhere near that same level of encouragement.)

The “special magic” might be service levels, innovative design, flexibility, customer friendly processes – any number of differentiators. In SCM, we need processes, technology, and attitude that supports these differentiators.

Companies that believe they have a special magic will decline to engage in commodity marketing. The customer who asks about price before learning about your services more likely than not is a commodity buyer.

No matter how well we are doing in our own minds, it is vital to test whether customers see us the same way. An important part of this involves assessing whether our SCM planning and execution processes are delivering successfully against our corporate strategies.

We can do a certain amount of this internally, but the acid test is to have an independent outside organization conduct studies and assessments. The next step is to do whatever redesign and technology reinvestments are needed to have customer assessments reflect our intentions.

Survival is pure and simple the end objective of risk mitigation and management. In the supply chain context, we must have capacity, technology, processes, production facilities, and supplier arrangements that promote business continuity.

Even momentary failures can undermine the foundation of a business, and the supply chain’s ability to continue to execute against corporate objectives.

Culture is a matter of making sure that the values of the enterprise are preserved and strengthened within the supply chain organization. Gaps and mismatches can easily weaken the strength of customer and supplier relationships that have been built on a strong foundation.

If SCM is not walking the corporate walk, key supply chain partners may begin to question in what other respects the enterprise might not be what it seems – or pretends – to be. The best writing we have seen on this topic is Harvard Business School Professor Jim Heskett’s 2012 book, The Culture Cycle.

In addition to working on his or her strategy skills, the supply chain executive needs to be a skillful planner – another new basic skill to be developed. Unfortunately, we have historically been perceived as problem solvers, fixers, and “deliverers”.

Your boss may not associate your job with strategy and planning; your challenge is change that perception. You should be concerned about finding enough competent labor to handle projected volumes—not just next month but in 2016.

You should be thinking about how much warehouse space and transportation capacity your company needs over the long term. Think carefully about the technology resources needed to keep your supply chain competitive for the next five years.

Computer software is always on the list, but also consider storage and handling equipment as well as order selection technology.

In honing your planning competency, consider the strategic questions that are likely keeping your boss awake at night:

- What are the megatrends in our industry?

- What changes are contemplated by our largest customers?

- How, where and when will our company develop new markets?

- What are our competitors doing?

- Where are we vulnerable?

- What is our most critical issue?

Finally, you need to clearly understand the main business goal of your company. Is it earnings, volume, or market share?

Answering these many questions is the best way we know of to demonstrate that strategy and planning are critical parts of your work life. And be proactive – don’t simply react to mandates from above.

An Exciting Space

As always, there is more. But the objective of this article is to illustrate the scope and range of today’s enablers of success that go far beyond what we would have imagined a few short years ago as part of the supply chain manager’s mandate.

Developing competency in the new fundamentals of supply chain management is a daunting task, we know. But it’s also a major part of what makes our profession the most exciting place to be now – and into the future. Good luck!

Art van Bodegraven is President, Van Bodegraven Associates, Practice Leader, S4 Consulting, and Development Executive for CSCMP. Ken Ackerman leads Ackerman Company.