By Dale Pickett | Supply Chain 247

As customer service requirements become more complex, supply chain optimization studies are the foundation for some of the most successful companies’ logistics and fulfillment operations. We look at the best practices behind supply chain optimization. In today’s demand driven, omni-channel world, it is easy to underestimate the complexity of global supply chains.

Yet the growth of global markets, increasing customer expectations, rising costs, and more intense and diverse competitive pressures are driving the development of new supply chain strategies and intricate network designs. That increasing complexity is exactly why supply chain networks need to be frequently re-evaluated.

In fact, a world class supply chain network is essential for product to consistently flow from the point of manufacture to the end user, regardless of the industry served. A well-designed supply chain network can significantly improve margins, support expansion into new markets, enhance the customer experience, and reduce operating costs. That applies to companies in all stages of maturity:

Growth-oriented companies, companies in transition, and companies with stable business operations can all benefit from distribution networks that are optimized to meet ever present challenges and opportunities.

While there are more tools available than in the past to perform a network analysis, there remain a number of important steps that must be taken. In this article, we present a blueprint for successful supply chain optimization.

It Starts With a Network

A world class, transformational supply chain begins with a network that employs an all encompassing view of the various business areas that manage delivery of products to customers. The result is significant capital, operational, and tax savings while achieving optimal customer satisfaction.

There are three critical elements to a world class supply chain network.

- Strategy Before Network. With complex and competing business goals—such as minimizing capital, improving operating margins, lowering the carbon footprint, and enhancing the customer experience—a clear and concise supply chain strategy must be fully aligned with your business strategy. Surprisingly, many companies begin reducing network costs before they define how the network can be fully leveraged to support the business strategy. Uncertainty in product mix and volumes, expanding markets, margin goals, dynamic customer service strategies, value-added opportunities, and product returns and obsolescence are just some of the considerations that are often given minimal consideration or overlooked entirely.

- Focus on Total Profit Optimization. An increasing number of companies are asking the question: “How can my supply chain be used to maximize profits?” This is a different objective than traditional network optimization projects, which define the objective as reducing costs and maintaining customer service levels. Currently, a combination of operating scenarios are required that drive alternative network models. Then sensitivity analysis is performed to evaluate impacts on how a company is working to improve the parameters it uses to drive shareholder value. Some examples include: EBIDTA, capital employed, working capital, operating expenses, tax effectiveness, margins, and cash-to-cash conversion.

- Project Versus Ongoing Process. World class supply chain networks evolve as sourcing adapts to market changes, product line performance varies, and companies integrate. A world class network incorporates an ongoing process that focuses on the flexibility of the supply chain and ensures that objectives are met consistently and over a range of market conditions while enhancing the key drivers of shareholder value.

Frequency and Types of Analyses

When an organization decides to evaluate its network, the internal leadership team must first address the type of effort that should be performed. Strategic reviews of a distribution network design often follow:

- a major business expansion, such as an acquisition;

- a change in business strategy, such as targeting new market opportunities; or

- the passage of time—a full review is typically needed every four to six years.

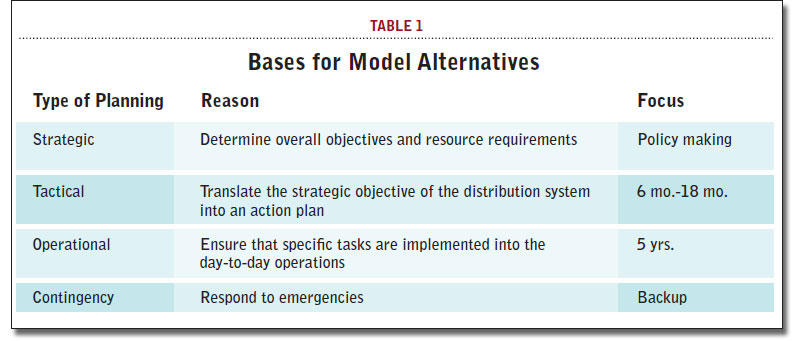

There are various methods of planning when it comes to guiding and positioning an organization. Planning needs to cover predictable and unpredictable circumstances. Without sound plans, a firm risks insufficiently anticipating problems and failing to implement solutions within the required lead time. With plans, a company becomes active and not passive. A good framework for planning is illustrated below.

Strategic Planning

Strategic planning is the process of deciding on the firm’s objectives. The goal of strategic planning is to define the overall approach to stocking points, transportation, inventory management, customer service, and information systems as well as the way they relate to provide the maximum return on investment. It addresses such issues as organizational structures, realignment of capacities, network planning, and impact on the environment.

Strategic planning is also a proactive tool designed to guard against predictable changes in requirements in which timing can be anticipated. This type of planning is directed at forecasting needs far enough in advance to efficiently allocate resources across the supply chain.

Granted, forecasting with a long planning horizon is a risky business, and distribution plans based on such forecasts often prove unworkable. Nevertheless, the forecast is a supply chain’s best available information concerning the future.

Tactical Planning

The tactical planning timeframe is one year to two years. Its primary purpose is to plan policies and programs, as well as to set targets to accomplish the company’s long-term strategic objectives. Tactical planning must anticipate the distribution center workload to prevent overloading the primary resource—the workforce—during peak demand.

In addition, the tactical plan defines how to develop the resources needed to achieve the goals in the strategic plan. For example, if a firm decides in its strategic plan that it requires a new warehouse location to enhance customer satisfaction, then the tactical plan allocates resources for the facility.

Tactical planning first attempts to provide timing for each step. Second, it considers major issues, such as identifying specific skills required to accomplish the plan and the time needed for each step. Third, specific capital requirements are identified for each step.

A fourth component is often the need for outside resources. In warehousing, this could mean anything from engaging a consultant to hiring a construction company. Other types of tactical planning include inventory policies, freight rate negotiation, cost reduction, productivity improvements, and information system enhancements and additions.

Operational Planning

Operational planning implements tactical policies, plans, and programs within the framework of the distribution system to devise the daily routine. An operational plan is where the rubber meets the road. Ironically, it is where the planning process is most likely to fail because the majority of the daily activities are routine. It becomes easy to lose sight of the planned goals.

The time horizon for operational planning can vary from daily to weekly to monthly. The major components of operational planning are managing resources—such as labor and capital assets—and measuring performance to aid operating efficiency and anticipate future operating issues. It can involve tasks such as: distribution center workload scheduling; vehicle scheduling; freight consolidation planning; implementing productivity improvements and cost reductions; and operations expense budgeting.

Contingency Planning

One of the most overlooked yet meaningful tools for sound distribution management is contingency planning. This is a defensive tool used to guard against failure resulting from unpredictable changes in distribution operations.

Typically, contingency planning asks “what if” questions. For example: “What if a major supplier is on strike” or “what if we had a recall” or “what if my primary supplier location is destroyed due to a major weather event?” The prepared manager will look to contingency planning to counter the potentially devastating impacts of the many emergency situations that may directly involve distribution.

Contingency planning is the opposite of crisis management (“putting out fires”), which entails developing a plan after something has occurred. The idea behind contingency planning is to significantly reduce the lead time required to implement a plan of action. You do not wait for a fire to start before installing sprinklers in the warehouse.

Events that can adversely affect a distribution system include:

- energy shortages,

- strikes,

- natural disasters,

- product recalls, and

- acts of violence.

Defining the Project Scope

Most business units within an organization are impacted by a network optimization. Therefore, senior leadership must understand and support which direction the project will take in order for it to be successful. This is where a clear definition of project scope becomes critical.

Prior to the project, the leadership team agrees to an overall business direction for the following categories.

- Sales – What direction is the company taking to increase sales? (Global expansion, acquisition, e-commerce, same store sales, etc.) Is marketing willing to reduce inventory to see the impact to customer service levels?

- Timeline – What is the desired recommendation date? This is tricky since it can result in a push to meet a date versus providing the best overall recommendations.

- Marketing – Are there changes in the business that will create a metamorphosis of product distribution, such as Internet daily promotions vs. bi-weekly store level promotions? Is marketing willing to reduce inventory if there is an impact to customer service levels?

- Production – Does production understand the impact of optimal manufacturing batches to inventory to locations?

- Finance – How critical is cash flow and the impacts to major investment?

- IT – Are there systems in place to give the necessary information for the analysis to be conducted properly? If not, agree to understanding the recommended approach from the support teams.

- Sacred Cows – Identify facilities, batch size, quality hold, product shortages, or other constraints that will not change in the foreseeable future.

- Sensitivity Metrics – This is a great time for the leadership team to identify metrics that should be considered for sensitivity analysis. This can include but not be limited to fuel costs, service time, planning horizon, and capital investment.

- Internal vs. External – Who should perform this analysis? Senior leadership must decide if it makes sense to perform the project in-house or to use an outside resource.

The distribution network planner must balance these conflicting needs to find the lowest cost distribution network and inventory management technique that satisfies both the customer and company objectives.

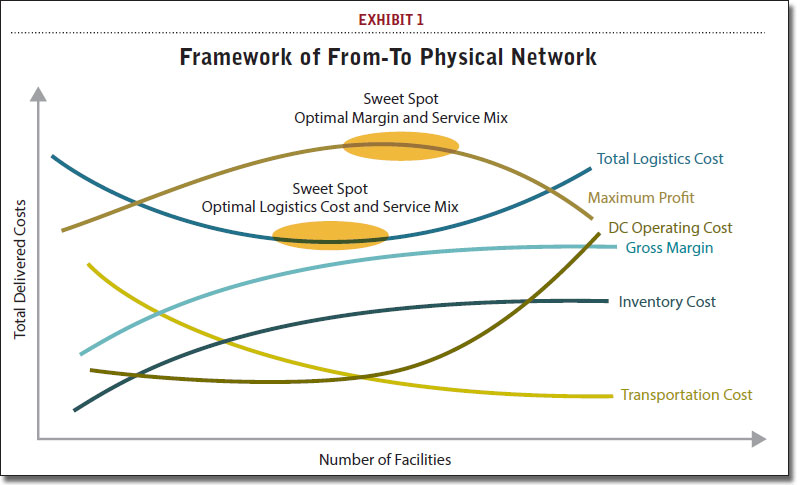

Exhibit 1 depicts the complexity that an end-to-end supply chain analysis should incorporate. Network planning and optimization that is founded on fact-based, quantitative analysis should be coupled with a review of processes, technology, and people that:

- Ensures alignment with the overall business environment and growth strategy to minimize costs and achieve desired service levels.

- Utilizes the best analytical tool for the individual project objectives.

- Analyzes alternative processes to maximize return-on investment while delivering improved operational metrics for customer service, inventory control, and transportation performance.

- Models the design with the intent to be refreshed as inventory policies change; transportation routes, cost, and service levels change; new products are launched; or suppliers change.

Key Network Components

All distribution networks have these key components: stocking points, transportation, inventory management, customer service, and ERP/MIS systems. Where and how these are located and managed will be determined from a network optimization.

Stocking points can be distribution centers, consolidation points, terminals, ports, return centers, or other points that receive goods from production plants or suppliers or are ship-to-demand points. Their job is to receive, store, pick, and ship product. Any point through which produced material flows to reach the customer is a stocking point.

Transportation includes movement from plant to warehouse, warehouse to warehouse, and warehouse to customer.

Inventory management is the purchasing and control of products based on a market forecast. Inventories are typically a buffer between vendors, production, and the customer to permit the system to accommodate unexpected variations in demand or production. Inventory management generally consists of forecasting requirements, procuring orders, and managing what is on hand.

Customer service is responsible for handling the key interactions between the company and its customers in order to assure customer satisfaction. It involves handling customer inquiries and order changes and managing other situations that occur in the customer/supplier relationship. Customer service may also include the ordering process. In addition, it is responsible for monitoring the goals management establishes for each product or market segment, (e.g., order fill rate, delivery time).

Management information systems (MIS) or Enterprise Resource Planning systems (ERP) are communication and/or control systems that support distribution. Their tasks range from taking incoming orders to managing fleet operations. In short, MIS/ERP systems process data to support the functions of the business. The types of systems most distribution operations make use of are:

- forecasting,

- budgeting,

- inventory management,

- order processing and invoicing,

- customer relationship,

- omni-channel communications,

- warehouse management, and

- transportation management.

Launching a Strategic Network Analysis

Once the leadership team understands the components of its network, has defined the scope of a project, and elects to do a network evaluation, the team responsible for the execution of the plan should begin the primary data collection for the modeling effort. It is not necessary to have everything prior to solicitations, but generally most reputable consultants will need the following information:

- Growth by organizational tier–formularized

- Sourcing locations and flow by SKU

- Outbound Flow by SKU to customer

- Trans-shipment movements between facilities

- DC cost metrics

- Outbound distribution\fulfillment costs (fixed vs. variable)

- Facility characteristics (size, staff, lease/own, drawings, equipment within, capacities

- Fleet characteristics(Internal vs. external)

- Published costs metrics (case/cube/lb)

- General Ledger accounts for the businesses units involved

- SKU listing

- Inventory by SKU location

- Expected start date and requested completion no later than date (three or four required alternatives)

Many times, this becomes a very challenging step. An organization must understand that evaluations require significant resources that recognize a sense of urgency but also a need to ensure that the information collected is accurate. There are costs and impacts to the accuracy of the network analysis if the beginning information is in poor condition.

Establishing and Communicating – “What We Do”

When kicking off a network analysis, team members often forget that one of the most important tasks is communication. Without communication, a plunge into the retrieval of information and direction to perform a network analysis will surely experience gaps and intensive rework.

The second task is to re-establish the scope of the project, taking into account any changes that have occurred to that scope. A third is to establish an executive strategies workshop. This should be a formal meeting in which the business leaders agree to the primary drivers and direction of the company.

Next, the team must document the existing network. It is critical to collect information from all sites being considered because the study could result in recommendations for closing, moving, or expanding them. Visiting those sites can be insightful. The following information needs to be collected for each site:

- space utilization,

- layout and equipment,

- warehouse operating procedures,

- staffing levels,

- receiving and shipping volumes,

- building characteristics,

- access to location,

- annual operating cost,

- inventory, and

- performance reporting.

In addition to facility information, the following information should be collected for the transportation system:

- freight classes and discounts,

- transportation operating procedures,

- delivery requirements, and

- replenishment weight/cube.

At the end of the data collection, a project team meeting is held to summarize the data collected and assess each site. This assessment will give the team insight into the operation and costs of the existing network. In addition, it will reveal information unknown to management that will be useful in developing alternatives.

Ideally, this meeting provides a “sanity check” to ensure that the information captured is representative of what will be modeled. Then the project team can provide a recommended aggregated plan to be reviewed by the entire team. This process of identifying assumptions will aid in information gathering and uncover any holes. Once everything is presented, the team can move forward with the analysis.

From the executive strategy session, an understanding of marketing strategies and sales forecasts should be applied to project the future state of the business. After all parties have conducted a view, this establishes the two baseline states for modeling purposes: current and projected.

Modeling the Status Quo

The steps just taken provide the information the team requires to determine the network operating requirements, the status quo. This involves examining the baseline cost and the service and performance characteristics of the current network. Key elements to be identified include:

- current facility locations, capacity, throughput, cost, performance, flexibility, effectiveness, and efficiency;

- inbound transportation costs from plants and suppliers;

- outbound transportation costs to customers and intra-company facilities;

- current inventory levels, in-stock percentages, and inventory carrying costs;

- delivery time to customers;

- current supply points for vendors and production facilities; and

- distribution of customer demand.

This information is developed into a model baseline from which alternative scenarios can be compared. Without the baseline, it is difficult to evaluate the costs and benefits of each alternative versus the status quo.

It is important to analyze and validate baseline information against information available from alternate and independent sources within the company. It is not uncommon for databases or database inquiries to yield incomplete results that would potentially skew the analysis.

Cost information should be compared against source documents, as well as the general ledger or profit-and-loss statements. Volume information from production or distribution should be compared with volume information from purchasing or sales. Graphical representations of network flows are useful to identify erroneous information that could be in the data. Stakeholders who would be affected by any changes in the distribution network will also want to review the baseline information to make sure that it represents the world as they know it.

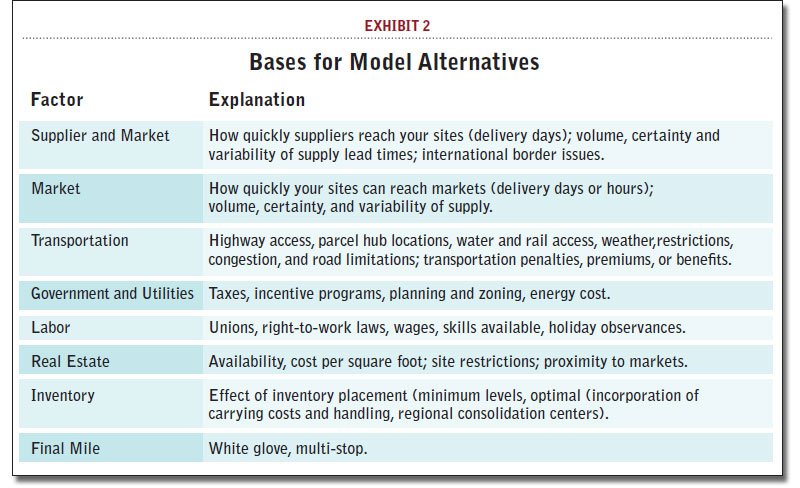

Developing Alternatives

Once the data has been collected and validated, the next step is to develop alternatives and operating methods. The inputs used to determine alternatives are site visits, future requirements, database analyses, and customer service surveys. The methods used for creation of the alternatives will vary. The main factors influencing site location are listed in Exhibit 2.

Modeling the Annual Operating Cost

The real value in network planning is the knowledge gained from understanding the workings of a company’s distribution system and applying imagination to the model in ways that will really benefit the distribution network. Facility alternatives can be close in cost, but range widely in other factors, such as service level capabilities. That makes it critical to have other criteria by which to judge the modeled costs, such as:

- Central administrative costs and order-processing costs.

- Cycle and safety stock carrying costs.

- Customer order-size effects.

- Inter-warehouse transfer cost.

- Negotiated reduction in warehousing and delivery costs.

There are several different approaches to network modeling (see sidebar below “Network Modeling”).

Regardless of which modeling method is used, the overall approach should closely resemble the following steps:

- Validate the existing network. Run a computer model to simulate the existing cost. Compare this cost with actual cost.

- Run alternative networks. Once the model is validated, run alternative networks for present volumes and forecasted volumes.

- Summarize runs and rank. Create a table to summarize costs by alternative. The table should list individual distribution center costs.

- Summarize all annual costs and service factors. Create a table that shows, by alternative, all cost and service factors.

- Perform a sensitivity analysis. This is based on the idea of setting up runs that fluctuate some components of the data. One might be a cost that is uncertain or has potential to change. By modifying this one parameter, the effect on the run can be determined.

- Determine all investment costs associated with each alternative. Look, for instance, at the costs of new warehouse equipment required to save space, expansion, and construction costs, or at any building modifications such as adding dock doors.

Determining Cost: The Economic Analysis

An economic analysis compares the benefits of a recommended network plan with the implementation cost. To perform this analysis, determine all the investments and savings associated with each alternative.

Cost considerations include:

- Personnel relocation

- Stock relocation (movement cost, model should have shown quantity)

- Computer relocation

- Taxes

- Equipment relocation

- Building components

- Inventory considerations

- Operating costs

- Severance

- Existing contracts

- Sale of existing facilities

- MHE or automation considerations

- Change in management

The result of this evaluation should be the ROI of each alternative compared to the initial baseline of the status quo. Once you have the economic analysis, perform a sensitivity analysis that fluctuates various costs and savings to see which alternatives are the most stable.

It is also a best practice to perform a qualitative analysis that looks at risk of factors such as customer service, ease of implementation, cultural considerations, profitability, and cash impact. These should be rated and presented as a topic for discussion.

Finally, once a conclusion has been reached, draw up a time-phased implementation schedule that lists the major steps involved in transferring the distribution network from the existing system to the future system.

Success is Not Simple: It is a Process

The output of a supply chain optimization project is a new plan for the network. A good supply chain network plan relies on a defined set of requirements. It should not be composed simply of ideas, thoughts, or possibilities. Possible requirements should be defined, analyzed, evaluated, and validated. They should result in the development of a specific set of strategic requirements. Normally, the planning horizon for such a plan is stated in years, with a five year plan being the most typical.

An effective network plan is also action-oriented and time-phased. Where possible, the plan should set forth very specific actions needed to meet requirements, rather than simply state the alternative actions available. Future sales volumes, inventory levels, transportation costs, and warehousing costs all come into play.

To get company leadership’s support for the plan, a detailed written document and maps should accompany the recommended action to describe and illustrate how the network will be implemented and how it will operate. The result should illustrate which strategy is best for the company because it maximizes profits to stakeholders.

If the plan answers the questions senior leadership team requested at the outset, and your company is prepared for this to become a process and not a project, you may be on your way to optimization success. And, the next time you admire a company’s seamless, cost-effective and customer responsive supply chain, think of the detailed network analysis behind it.

Network Modeling

There are three categories of network models.

A Centroid analysis calculates the weighted center of customer demand by using map coordinates and customer volume. It was one of the first methods used to determine new site locations, but it is inadequate when compared with today’s modeling techniques. Centroid analysis can be done on paper and assumes things like transportation costs are proportional to distance. It ignores capacity constraints, service requirements, and differences in transportation and facility processing costs.

Optimization models come in a wide variety of complexity and sophistication, with prices to match. They are typically linear or mixed-integer programs that are capable of determining an “optimal” distribution network based upon the data, assumptions, and parameters provided. Changes to any of the assumptions, parameters, or data will cause the model to yield a different result. Therefore, they are very dependent on the quality of the data and parameters and the experience of the individual performing the modeling analysis. An optimization-modeling program is more sophisticated than a Centroid analysis, but it is limited to evaluating a static range of variables. If a network can be described by summarized data, or by looking individually at one or more slices in time, then an optimization model is very effective.

Simulation models, like optimization models, come in a variety of sizes and shapes. Unlike the optimization model, which starts with a set of data and gives a single answer, a simulation model will start with a single answer—a network alternative or scenario—and examine the impact on the scenario of a variety of kinds of data sets, over time. Simulation models are very useful for determining the impact of supply or demand variability, network constraints, and bottlenecks on the efficient operation of the network. Like optimization models, they are very dependent on the quality of the inputs and the skills of the modeler. However, they are able to better represent the volatility a company faces in the real world.

To determine the model that is right for your optimization project, a planner needs to determine how important it is to include complex variables, or if assumptions and averages can provide sufficient grounds for decision making.